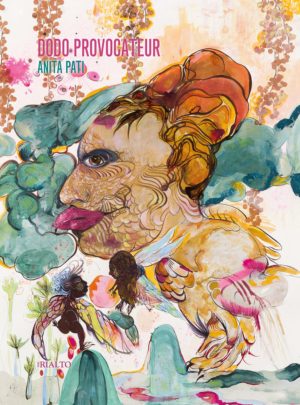

Anita Pati’s prize winner pamphlet, which we published in the first week in September, had it’s London launch on September 24th at The Poet an aptly chosen pub in Baring Street (N1 3DS). I put the post code in because I must have been one of the last people in London, without SatNav, or Wayz on my phone, to drive around Islington navigating with a copy of the A to Z on the passenger seat. Anyway it was a cheerful evening. In case you still haven’t connected with this pamphlet here’s what some important people have said about it.

‘Every poem in Dodo Provocateur is taut with riotous language, utterly surprising and dizzyingly ambitious. Yet despite their linguistic fanfare and creative formalism they are ultimately poems which engage with and reframe the outsider – giving voice to the lost, the ignored and the marginalised. Dodo Provocateur is a series of moving vignettes, which celebrate the unrealised beauty of Victorian Sewer Pumps, crime scenes, earwigs and extinct birds. This pamphlet represents a significant body of work from an important, articulate and restless new voice in British poetry.’ Richard Scott

‘In her explorations of displacement, alienation and fractured identity, Anita Pati engages unique sprung rhythms and invented dialects – as though she hears a music no one else has access to. Her poems are strange, risky, exciting and utterly original.’ Kaththryn Maris

‘Whether cataloguing a species’ slow demise or a child’s stirrings in the womb, Dodo Provocateur is an exuberant box of treats, full of life and linguistic gusto. Flipping effortlessly between distant colonial horizons and the house next door, Anita Pati is a real original: a poet whose wry humour and slant perspectives on the world don’t fail to surprise and delight.’ Sarah Howe

‘In Dodo Provocateur, Anita Pati’s voice has emerged as original, provocative and restlessly reflexive. Addressing themes and subject matter ranging from childhood memories to extinction, racism, Jimmy Savile and the Pendle witches, the expression is crisp and striking and each poem partakes of a lexical virtuosity that echoes Fran Lock, Geraldine Clarkson and Imtiaz Dharker. These poems are not satisfied and they quietly push the boundaries.’ Steve Ely

‘Anita Pati’s poems sound entirely her own. Every line in Dodo Provocateur brims with music and meaning. These playful poems explore racism and patriarchy in Britain – a land of Shepherd’s Pie, Shakespeare, Kwik Save and crime scenes – via an astonishing range of characters and forms. But in this least auspicious of places, Pati still manages to winkle out reasons for hope. We are lucky to have such ‘knuckly flowers’; such ‘beetley treasure’.’ Clare Pollard

STOP PRESS NEWS: Dodo Provocateur has been shortlisted for the Michael Marks Award. Results will be announced on December 10th.

Dodo Provocateur is available here

The Rialto 92

A friend, a reader and writer of poetry, said to me last week that the current issue of the magazine is the ‘most interesting and excitingly readable poetry magazines around at the moment.’ This is not an opinion that has been widely publicised, partly we think, because we printed the issue at a time in the summer when many people were thinking to go on holiday – that after exams lull when a rest from reading becomes compulsory nation wide. Or it may be something to do with the Brexit effect which is steadily stealing people’s lives and rendering them unable to think or talk about anything else.

I want to take this opportunity, as well as to re-iterate my thanks to Edward Doegar and Degna Stone who worked with me on the selection of the poems, to endorse my friend’s recommendation and to look with you at a couple of poems in the issue. ‘For too long poetry has had a reputation for being overly difficult, elitist and obscure. Yet it seems to me that nothing could be further from the truth.’ Thus says John Burnside writing in The Guardian (October 5). And here is a poem that surely backs him up.

NIGHTINGALES

Who wouldn’t feel a bit low

biking back into town again

from another vain after supper

ride round our nightingale woods

where they’re two or three weeks overdue,

and though it’s worrying what we’ve done,

it’s a warm still evening – perfect

for hearing them sing – and being

in no hurry to go in

I pedal on past my turning

to check if it’s true our local

The Volunteer, shut up for years,

against the odds has reopened,

and yes, it’s alive, lights, music

and inside this Saturday night

as I swing round the corner

a good crowd of mostly young men

in both bars with more arriving

down the side street, one of whom

in reply to my Evening calls out –

Take your beret off, you cunt.

Michael Laskey

(The Rialto, 92, page 11)

This is a shocking poem, and it is beautifully put to together. There are four five line stanzas with a single flying last line; Michael uses a minimum of poetry devices, alliteration – for example three ws in line one and again in line five, two bs in line two and two rs in line four, etc; and then there’s rhyme, ‘again’/‘ vain’, ‘low’/ ‘town’ in stanza one, with stanza two having several ‘ing’s and an ‘in’. And there’s a lovely hinge where the long line at the end of stanza one matches the long line at the start of stanza two. But what is glaringly apparent is the accessibility of the syntax and the vocabulary: it’s so clear what’s going on, the poet is returning from one adventure, looking for nightingales, and sets off on another one, to check on the ‘Volunteer’ pub. Two stanzas to each task (there’s so much balance in the four stanzas of this poem – like riding a bike maybe?), but there’s surely nothing ‘difficult’.

A word about the title: the most famous nightingale poem in the British tradition is Keats’ ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, and the nightingale is persistent through European tradition (there are nightingales in the grove in Colonus where Oedipus dies, and, of course, Juliet says ‘It was the nightingale and not the lark’). There is no need for the reader to know all this to get the impact of Michael’s poem. However the opening line is ‘Who wouldn’t feel a bit low’, which is a delicious understated step backward from Keats’

‘My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk…’ and so on

So, the first two stanzas are about loss and the environmental degradation/ climate change that we are enduring. It’s a ‘warm still evening – perfect/ for hearing them sing’, but they aren’t there and the poet/narrator turns his curiosity to a rumour about a local pub, and cycles off to investigate. We move from change in the wider world to change in the local world. It’s noticeable how the pace quickens in this second half, we still have the same eight syllable lines, but instead of the languor of ‘warm still evening’ we have the sharpness of ‘yes, it’s alive, lights, music’ and the movement of ‘swing round’, ‘more arriving’.

We now come to the climax of the poem, its last two lines. What we know so far about the poet narrator is that he’s an energetic kind of bloke (possibly no longer ‘young’ (St. 4 line 2)), who likes to go for a bike ride after tea round the neighbourhood he knows, that he’s alive to environmental concerns, admires the song of nightingales, recognises they’re a diminishing species: but he’s also part of his town (has a ‘local’) and is awake to the health of his community and happy to join in the celebration of a summer evening at the pub. However his cheery shout of ‘Evening’ gets the reply ‘Take your beret off, you cunt’. Raucous street language, or something more? Michael, who is very good at the ‘show not tell’ kind of poetry, leaves interpretation entirely up to the reader. The ‘young men’ whose song is very different from that of the nightingales, nevertheless sing in a way typical of their species at that stage of their development. Is their objection to the ‘beret’ anything more than youthful mischief? Whatever you think the poem is ‘about’ there’s a great deal packed into its twenty one lines.

There’s another remarkable poem by Michael Laskey in this issue, ‘Between Ourselves’ on page 21: impossible not to love both pieces of work. Final note about ‘Nightingales’: pubs named ‘The Volunteer’, I learn from the internet, can get their name from the establishment, during the Napoleonic Wars (when their was a perceived risk of invasion from Europe) of the Volunteer Corps, officered by gentry and manned by tradespeople and keen to repel foreigners (whatever their headgear).

This Newsletter is turning into an essay. Before I get on with the News I just want to look for a while at another poem that I like in 92. This is a poem by Amaan Hyder. It’s eight eleven line stanzas long (plus a final two lines), so I’ll, unfairly, precis my remarks. Here are the first two stanzas.

WHAT LANGUAGE DO YOU SPEAK AT HOME?

In 2004, I come out to you.

A cousin is getting married.

There is family staying.

It’s poor timing.

I’m told you are really struggling with it.

I say to you, in order to ease things,

that I’m actually unsure, that I shouldn’t rush into this.

So we leave it at that. What’s good

to come out of this is that we can be open now –

this is what I say but we don’t talk about it,

have not talked about it, for fourteen years.

Now I have had a boyfriend for four years.

I have not mentioned him to you.

The world has changed since 2004.

Time has passed. You have retired.

You are less stressed. It is easier

for you to become unwell. I think if I was

to come out of the closet again it would be easier,

but I look back to what happened before.

I go back to my default which is not to speak,

to hide, to give space to those around me.

I don’t want to change your life.

Amaan Hyder

Start with the title, which is admirably packed with meaning. It’s surely not uncommon, growing through childhood into adolescence, to have a sense that you and those you share your home with don’t speak the same language, that you and they inhabit separate realities. This poem is about this. It is also, as Amaan’s community has Asian origins, about a literal difference between languages, between English and Urdu. And again it is about the difficulties of conversations between straight and gay communities. And there is also, I’m sure, behind the title that darker question, ‘Where do you really come from?’ Multilayered.

One of the things I find exciting about this poem is the use of short sentences. They look to be simple but are in fact skilfully crafted. They freshen up the commonplace phrases – ‘poor timing,’ ‘really struggling,’ ‘shouldn’t rush into’ – that are the staple of this poem’s language, its clarity and accessibility. It’s such down right likeable piece of writing. And the poet comes across as being good hearted, generous and kind. It’s intelligent poetry, I commend it to you.

We still have copies of issue 92 available here.

The Rialto 93

Is advancing towards readiness. A little of what’s in it? Well there are some new poems by Hannah Lowe, and there are poems by each of the shortlisted poets from the last pamphlet Competition: altogether 43 poems so far so we are well on the way.

Nature Poetry Competition

We have launched (December 1st) our newest Nature Poetry Competition. The closing date will be May 1st 2020: the judge this time is Pascale Petit (whose long poem ‘In The Forest’ was such a star start to R 92). Full details are up on the website and there will be a flier in the next issue of the magazine. I was remembering this morning how much I enjoyed compiling the Whitgift School Selborne Society’s Annual Report of Birds of the Croydon Area. It was certainly preferable to doing most of the schoolwork. Nature has become centre stage in the world of politics. We seem to be waking up to the knowledge that we are poisoning the planet and ourselves and also to the knowledge that we have a responsibility to the (diminishing) multitude of life forms that we share the planet with. All of which is to say that we welcome poems from the width and breadth of your contact with Nature. We are once again working in association with the RSPB, Birdlife International, and the Cambridge Conservation Initiative (CCI). There will be a celebratory reading with the winning poets and Pascale at CCI in September.

Pamphlet Competition No. 3

Will be soon open for Submissions.

Subscriptions

With the next issue we will be increasing our prices. Always a difficult subject. As you know we have for most of our history had a discounted subscription rate for anyone on a low income. This we will be continuing to do. I know what it is to be unemployed or to be working in low paid work with no sense of getting anywhere. I am also very aware of the way that the gap between the living standards of richer people and of the rest of us has stretched and stretched. Enough. The prices we’ve so far decided are as follows.

The Cover Price will go up to £9 per copy.

The UK Subscribers’ rate will be £25 for three issues.

The UK Concessionary (Low Income) rate will be £19 for three issues. We don’t require proof of your status, you can self-assess this.

The Rest of the World Subscribers rate will be £45 for three issues.

The Europe Subscribers’ rate is yet to be decided (as is the nation’s relationship to Europe).

For Institutions, (Libraries and Universities etc.,) we are introducing a new multi-use rate

of £60 for three issues. We’ve been generously out of step with other magazines forever…

Costs for Single issues (UK, Europe, Rest of the World) will be posted on the website shop once we have researched them.

Those of you whose subscriptions are currently (R92) needing renewal (and thanks to all the prompt renewers) can still renew at current prices.

Midwinter

It will soon, once again, be St Lucy’s Day (Friday 13th December, day after the General Election). Seasonal Greetings and thanks to you all.

Michael Mackmin