A Brief history of the Rialto

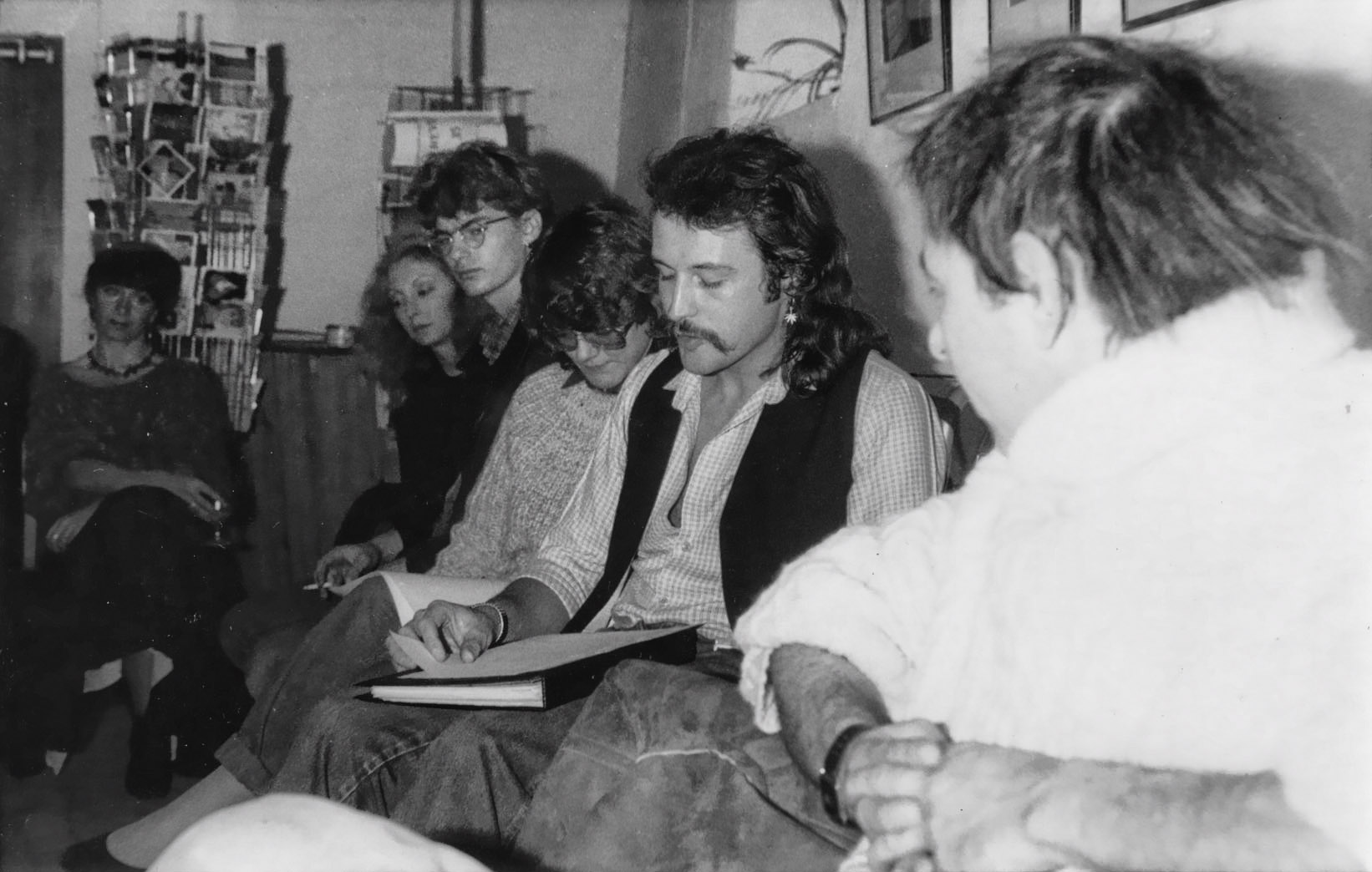

We did fund raising – jumble sales, music gigs. Jenny’s dad, co-editor of Samphire (famous in its time, just about makes it onto Google now) offered us, with great generosity, access to their subscriber list. A loving friend, still anonymous, paid the printing bill for the first issue. We let the poetry world know that we were making a poetry magazine where new poets would appear alongside established contemporaries. Poems and subscriptions arrived. We recruited an art editor and put together the first issue. Some of the poems were by our friends and relations, but we also had work by Margaret Atwood, Miroslav Holub and George Barker, four poems by a youngster called Carol Ann Duffy, and poems that arrived in the post from, for example, Evangeline Patterson and Glen Cavaliero. And it was fun to do.

We did fund raising – jumble sales, music gigs. Jenny’s dad, co-editor of Samphire (famous in its time, just about makes it onto Google now) offered us, with great generosity, access to their subscriber list. A loving friend, still anonymous, paid the printing bill for the first issue. We let the poetry world know that we were making a poetry magazine where new poets would appear alongside established contemporaries. Poems and subscriptions arrived. We recruited an art editor and put together the first issue. Some of the poems were by our friends and relations, but we also had work by Margaret Atwood, Miroslav Holub and George Barker, four poems by a youngster called Carol Ann Duffy, and poems that arrived in the post from, for example, Evangeline Patterson and Glen Cavaliero. And it was fun to do.

My vision for poetry was that the magazine would be in newsagents nationwide (I remembered watching Jon Silkin persuading reluctant newsagents in Jesmond to stock Stand): so our A4 format is partly to enable The Rialto to sit comfortably alongside Vogue; we also chose it so that poems could have space to breathe in. We decided against reviews because we thought they perpetrated partisan orthodoxies. ‘The Republic of Poetry’, was John’s vision.

Money, and how to raise it, became part of our conversations (it’s still there in the foreground). Once we’d shown what we could do the Arts Council, through its regional office in Cambridge, began to support us. Something they’ve continued to do, with the occasional hiccup, ever since; without them we’d have dipped out years ago I suspect – the money is important, but what’s also important is the confirmation that what we are doing counts. During our first visit to the Arts Council office in Cambridge George MacBeth, who was an advisor there, told us that we should pay for the poems we published, ‘even if it’s only a fiver a poem’. He considered it a vital gesture of respect, and that we’d help poets to respect themselves if we gave them money.

I’d like to pay poets more– the fiver has grown into £20 over the years, but has been stuck at that rate for some while, way short of the minimum of £200 per poem that I think we should pay. Payment respects the craft of poetry, the amount of work that goes into shaping a poem, the amount of work that goes into shaping a poet – the sheer mass of reading that you have to do to get poetry inside your skin, for example. And payment also acknowledges our deep belief in the importance of poetry, the way poetry helps safeguard language so that language can continue to help humankind make sense of itself and of life.

So, the magazine grew in popularity both with poets and readers: after the seventh issue Jenny Roberts, who had adopted two small children left us, but not before she’d helped us to recognise the excellent new poetry being written by women. Women poets continue to be strongly represented in The Rialto. In 1996 John Wakeman left the magazine and the country. His wife, one of the first women to be ordained in the Anglican Community, became minister for three Church of Ireland parishes in West Cork. John was quiet for a bit, then started The SHOp, a magazine which he and Hilary ran until the end of 2015.

The Rialto continues, we are now approaching issue 100. During this time there have been (and continue to be) other projects. Before he left John edited How it Turned Out, a collection by his friend Frank Redpath. I liked the idea of doing books and in 2000, with help from the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation, we published In by Andrew Waterhouse and Diverting the Sea by Emily Wills. In won the Forward First Collection Prize. We published a few further collections, two of which, The Doves of Finisterre by Julia Casterton and Helena Nelson’s Starlight on Water, won the Jerwood/Aldeburgh prize. We moved on to publish our Bridge Pamphlet series, with which we hope to help poets bridge the gap between appearing in magazines and getting a first collection published. This has certainly worked for three of the poets, Lorraine Mariner, Richard Lambert and Hannah Lowe – only a matter of time for the others (and meanwhile Laura Scott’s What I Saw won the Michael Marks Award).

We have improved the appearance of the magazine year on year (it’s now perfect bound and the 64 pages are printed on better, more sustainable paper). To begin with we had art editors, mostly connected with what was then called the Norwich Art School, to advise us, but for most of our history the look of the thing has been down to Nick Stone, formerly of Printing Services (Norwich) now of Starfish Ltd, and one of our Trustees. Nick is also responsible for the website and for running our various Social Media pages. We can, by the way, only afford the excellence of appearance that we’ve achieved because Nick does a lot of work for love for The Rialto. And the same applies to all of our editors, trustees and board, and to yours truly.

We have improved the appearance of the magazine year on year (it’s now perfect bound and the 64 pages are printed on better, more sustainable paper). To begin with we had art editors, mostly connected with what was then called the Norwich Art School, to advise us, but for most of our history the look of the thing has been down to Nick Stone, formerly of Printing Services (Norwich) now of Starfish Ltd, and one of our Trustees. Nick is also responsible for the website and for running our various Social Media pages. We can, by the way, only afford the excellence of appearance that we’ve achieved because Nick does a lot of work for love for The Rialto. And the same applies to all of our editors, trustees and board, and to yours truly.

However, our hard won funding has enabled us to employ a number of freelancers over the years, notably Dean Parkin, Nathan Hamilton, Helen Mitchell, Katy Carr, who have been invaluable in helping us to negotiate successfully with ACE. They’ve also been involved in promoting our marketing skills, Nathan in particular pushing us towards closer contact with Social Media. (By the way Nathan’s Dear World and Everyone In It, Bloodaxe, 2013, began life as a series in the magazine). Particular tribute is due to Helen who tactfully guided the editor into more business-like thinking streams. She also created our immensely helpful Advisory Board. This group, Matt Howard, Claire Kidman, Colin Hughes, Esther Morgan, Nick and I, meets at least quarterly to review our progress. More details of the members can be found in the Who We Are section of this site. Helen also managed two very successful grant applications, and was instrumental in the creation of our latest project, the Editor Development Programme.

The Editor Development programme, run in its first phase in partnership with The Poetry School and in its current phase in partnership with Writers Centre Norwich, gives opportunity to two members of the poetry community to work as Assistant Editors, mentored by the editor. They assist in the selection of the poems for two issues of the magazine, and in putting the magazine together, etc. For the second magazine they take responsibility for at least 15 pages of the contents. There are seven graduates from this programme, Fiona Moore and Abigail Parry, Rishi Dastidar and Holly Hopkins, Will Harris, Edward Doegar and Degna Stone. Graduates then have the opportunity to continue their relationship with The Rialto. Fiona worked as co-editor with the magazine for several issues, Abby edited two of our pamphlets, Richard Scott’s Wound and Kate Wakeling’s The Rainbow Faults. Will, Rishi, Degna and Ed will all be editing individual publishing projects during 2021 and 2022.

In autumn 2015 we returned to publishing First Collections with the successfully crowd-funded The Swan Machine by Dean Parkin, who was for several years Artistic Director of The Poetry Trust. We’ve also in recent years run, in conjunction with the RSPB, Nature Poetry Competitions; the first was judged by Sir Andrew Motion and Mark Cocker, the second by Ruth Padel, and the most recent ones by Simon Armitage, Pascale Petit, and Daljit Nagra.

We continue to believe in the Republic of Poetry, and in the fundamental importance of poetry as the art form most likely to preserve humane values in our culture.

Michael Mackmin